L.S. Lowry

The dark side of the matchstick man

Artist L.S. Lowry never married or had a girlfriend.

But the woman he befriended as a child now tells of their bizarre relationship.

Life in the nineteen fifties was less complicated than it is today, and people were less prone to pointing the finger of suspicion.

In our modern world, it would be difficult for some people to easily accept a friendship between a young girl and a gentleman some 57 years older;

this was the situation regarding Mr L.S.Lowry and Carol Ann Lowry.

Their meeting was a result of Carol Ann's mother suggesting that her daughter, who was 13 years old at the time,

wrote to Mr Lowry, explaining how she had always wanted to become an artist.

To their amazement he turned up one day at their home, and a friendship began that was to last a lifetime.

It changed the course of her life and the two Lowrys - although not related - formed a friendship that was part uncle and niece, part mentor and pupil.

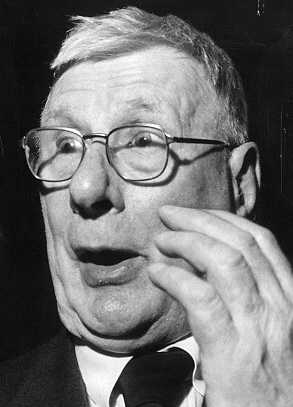

My fairy godfather: A teenage Carol Ann Lowry on an outing with her friend and namesake, the painter L.S Lowry

Nothing was said against it. Indeed, Carol's mother Mattie, who was separated from her father, encouraged the relationship,

and Lowry, who had never had so much as a girlfriend, took her on outings - especially to the ballet.

He treated her to meals in restaurants and holidays by the sea. She called him 'Uncle Laurie'.

It ended after nearly two decades when, in 1976, he died of pneumonia, aged 88.

Only then did news of Carol's existence reach a wider public.

Lowry had bequeathed his entire £300,000 estate to her, together with a substantial collection of his own paintings, themselves worth a fortune.

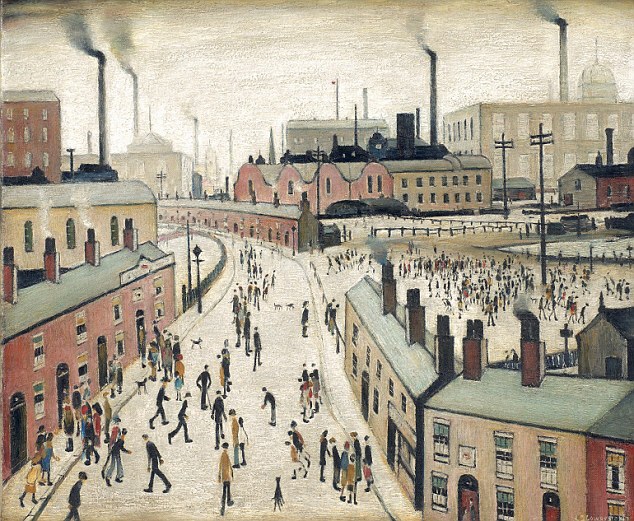

Lowry's townscapes are some of the best known and most popular works of the 20th Century, evoking both nostalgia and curiosity.

His crowds of matchstick people hurry through the northern industrial landscapes of his childhood, a vision of shared activity tinged

with individual loneliness. Carole has plenty of these, as well as some of the seascapes and portraits for which he is also known.

Fond memories: Carol Ann has not talked about her life with the painter until now

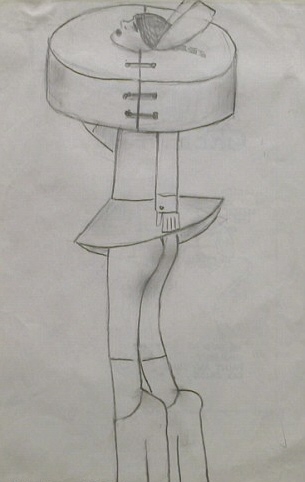

But her private collection contains a different sort of artwork too, drawings without a street scene anywhere in view.

Instead, these portray girls or women in an array of bizarre and confining costumes. Although by no means pornographic,

the sexual edge is clear. To many Lowry fans they will be downright disturbing.

They suggest a new, somewhat unsettling dimension to his relationship with women, including Elizabeth, his controlling mother,

and to his view of the world in general, so often - and wrongly - viewed as cosy.

Carol was 32 when Lowry passed away; she has always guarded her privacy with care and continues to do so now.

She has said little about her relationship with Lowry and even less about the secret art collection. But now she has agreed to

speak about the paintings and their author for a major TV profile of the painter, the first time she has done so in more than 30 years.

Carol, now in her 60s, has also allowed the disquieting pictures - many of which have never been seen in public before,

let alone by a mass audience - to be revealed to the world.

Her collection remains as she inherited it. The works are unframed, kept in large folders and separated one from the other by tissue paper.

They include a notebook of sketches of Lowry's stick-like people, familiar industrial scenes and an astonishing collection of provocative,

in some cases almost sadistic drawings of puppet-type women with pointed breasts and high, tight collars, who look as if they have been

squeezed into an invisible narrow tube.

It is not surprising that Lowry, a shy man, repressed even, wanted them kept secret while he was alive.

'The unseen drawings certainly shocked me when I first saw them,' Carol admits, 'especially as he had only ever behaved like an uncle or

grandfather towards me. But if he hadn't wanted them displayed he would have destroyed them.

Hidden images: Some of Lowry's remarkable exotic drawings from Carol Ann's private collection

'I remember he repeatedly said to me, "They can say whatever they like about me after I am gone".

They are part of his work and I think it is time now for them to be seen.'

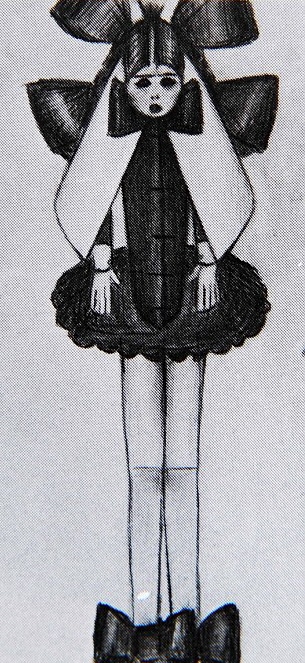

Her own analysis is that they reflect his strange fascination with the ballet Coppelia, which is about a life-size mechanical doll.

Indeed, Carol suspects that Lowry had a deep-seated wish to control her in the same way.

'He was very keen on the ballet and repeatedly took me, and sometimes a friend, to see it,' she explains.

'I have often wondered why he took me so many times and wondered whether it was because he liked to control me, like a puppet master.'

Plainly, though, there is no resentment.

'It was only in a guiding way,' she adds hastily.

'He was interested in everything I did. He liked watching my reaction to things, enjoyed listening to me and my friend talk, and watching

us develop. He was the king of people-watching.'

Groundbreaking: One of Lowry's typical 'matchstick men' paintings, depicting the industrial north of England

Many of the drawings appear to contain some element of force, or even violence. Certainly, they pose questions. Were they, perhaps, his way

of getting back at a mother who exerted a vice-like grip over him throughout his life, or even at women in general?

'All my people are lonely,' Lowry once said, 'and crowds are the most lonely thing of all,' a comment that is hard to dissociate from the man himself.

An only child, Laurence Stephen Lowry was born in Stretford, Lancashire, on November 1, 1887. During his childhood his mother,

Elizabeth, constantly told him how disappointed she and his father Robert were that he wasn't a girl.

The family lived in Pendlebury, in Greater Manchester, and Mrs Lowry, who had wanted to be a concert pianist, was permanently unhappy

with her lot. She relentlessly criticised Lowry and if he or her husband, an estate agent and an undemonstrative, weak man, didn't do what

she wanted, she would manipulate them by feigning illness and taking to her bed.

The crueller she became, the more Lowry yearned to please her.

He did not make friends at school, never passed his exams and was both gauche and shy.

There are plenty of theories about his reclusive behaviour.

Professor Michael Fitzgerald, a Dublin psychiatrist, for example, believes Lowry was autistic.

Others suggest that the artist constructed a careful facade, a wall of emotional control as protection from his mother's relentless criticism

and rejection. Michael Simpson, the head of galleries at The Lowry museum in Salford Quays, is in no doubt about the sexual undertone of the

newly emerged drawings, even if his explanation is rather more matter of fact.

He says, 'I date them between 1972 and 1974, just a few years before he died. It was a time when young women in miniskirts were occupying the

High Street and Lowry, by then well into his 80s, was obviously fascinated by what he saw.'

Erotic; The drawings, which squeeze women into constrained outfits, represent a marked move away from Lowry's traditional works

'Lowry was born into the Victorian age. He was still with us in the Seventies, saw society changing so much around him and I think they

appealed to his darker side. Everyone has one and Lowry is not alone in using his art to articulate this aspect of his sexuality.'

When Lowry failed so consistently and miserably at school, his parents sent him to art classes in the evening to find out if this, at least,

could be something he was able to do. He took it seriously, became a first-rate draughtsman and painted a remarkable portrait of his father in

1910, and of his mother two years later.

There were, however, no thoughts of Lowry becoming a professional painter. Instead he became a rent collector, painting at night after work from memory.

It was a routine he maintained for 40 years. Lowry's father died of pneumonia in 1932, leaving considerable debts. His mother then took

to her bed, where she stayed for seven years, totally dependent both physically and emotionally on her son.

His paintings were by then slowly attracting attention and, aged 52, he had a breakthrough.

Sixty of his works sold in an exhibition and one of them was bought by the Tate. It was something his mother was too self-obsessed to recognise.

When she died in 1939, he was devastated, becoming so depressed he considered suicide.

'I have no family, only my studio,' he said at the time.

'Were it not for my painting, I couldn't live. It helps me forget that I am alone.'

During this wretched period he painted a series of angry, red-eyed self-portraits. He also lost interest in his surroundings,

neglecting the family home so much that, nine years after his mother's death, it was repossessed by the landlord.

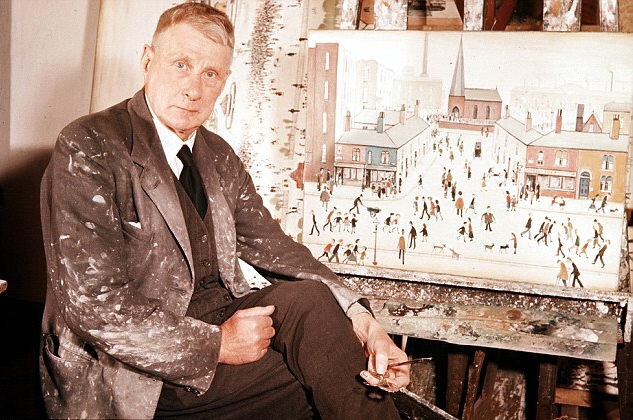

Secret life: L.S. Lowry, wearing one of his trademark paint-flecked jackets, at work in 1957

Lowry then moved to Hyde in Cheshire, where he stayed for the rest of his life.

He was 70 when he received Carol's letter in 1957. He initially didn't reply, but months later, feeling lonely, he read it again

and on impulse jumped on a bus, turning up unannounced on her doorstep in Heywood, Lancashire.

During her interview for the programme Perspectives: Looking For Lowry, Carol recalls her first impression of the artist.

'He was very Victorian-looking, with a waistcoat and big hands. Sometimes, later, he would turn up with white paint on his clothes.'

She thought him 'wise, fascinating and interesting', and a bond between them was quickly formed. The relationship satisfied a need in both of them.

Lowry discovered someone he could care for and about, and who, perhaps, satisfied his longing for a family, while Carol found what

she describes as a 'fairy godfather who came along with gifts, not merely material gifts, but gifts of character and education'.

Thirteen was an impressionable age, especially for a child of the Fifties, and Carol has admitted she also had an impressionable nature.

'I cannot help but feel it was fate that brought us together, that enabled each of us to fulfil a need in the other,' she says.

Lowry offered to pay her fees at the convent she attended, helped with the rent and arranged for her to attend Saturday morning

classes at Rochdale College of Art.

Eccentric; Lowry never married ir had a girlfriend, and spent his life thinking that he had failed his mother.

Carol has not spoken about her mentor since the years immediately following his death, when she helped with Shelley Rohdes's well regarded book 'L.S. Lowry, A Biography'.

'At first, and it sounds awful to say it, he was to me just a person with endless supplies of money,' she said at the time.

'He would come and give me not presents right away, but visits to Manchester, which was something wonderful. We would go and return by

bus and sometimes by taxi, and eat in restaurants and talk and talk.'

Her father had been a cotton spinner and 'Uncle Laurie' enjoyed hearing tales of the mill and of how her dad had come home to soak his feet after work.

'He seemed to be my friend straight away. He treated me as a child, but in an adult way. He never talked down to me,' she said.

She remembers him getting angry with her only once, when she said she'd like to go to Somerset House and find out if they were related.

'He told me not to and when I repeated it, he thumped the table in the cafe where we were having tea and said, "You will not do it, Carol. You will not".'

She obeyed him. Later, she thought he had probably checked for himself.

As time passed, she came to enjoy his company, to love him, even. There was only one moment when his immaculate behaviour towards

her wavered, if only slightly.

When Carol was 15, the unlikely couple went on holiday to Sunderland together.

Every evening, Lowry escorted her to her bedroom and then returned to the hotel lounge.

One evening, just as she was closing her bedroom door, he asked: 'Do you trust me yet?' She replied, 'Nearly'.

It was an unusual question and a strange place to ask it.

She is quite clear, however, there was nothing untoward in his intentions;

'Very much later, when I was grown up, people put it into my head that he might have felt differently towards me, as a man feels towards

a woman, but I absolutely cannot believe it to have been so. I don't think there was ever a physical thing for him, with any woman.'

Ten years after they met, his painting 'Coming Out Of School' was chosen to be a postage stamp. All 11 million stamps sold out within weeks.

He was by now financially comfortable, buying paintings by artists including Honore Daumier and Lucien Freud, but it was pre Raphaelite Rossetti

who was his favourite.

'Rossetti women are not real women. They are dreams,' he once said.

Lowry continued to write to Carol and visit her regularly while she was in Swansea, training to be an art teacher.

He settled a five figure sum upon her once she qualified.

Then, in 1970, he made his will in her favour.

In 1974, she married on the Isle of Wight where she was teaching. She has never said what her new husband John made of the unusual

friendship but he seemed happy enough to visit the elderly artist.

Although Lowry didn't come to the wedding, he regularly invited the couple to his home and made no attempt to change his will.

During the last 20 years of Lowry's life, his paintings were bought for six figure sums by Royalty and renowned galleries.

In 1968, he was offered a knighthood but turned it down.

He was called a genius but he always felt he was a failure because his mother told him so.

Modern master; Today, Lowry's paintings sell for hundreds of thousands of pounds and are displayed in major museums.

He died just a few months before a major exhibition of his work was held at London's Royal Academy.

It drew more than 350,000 visitors, breaking all the Academy's records. Now his paintings sell for millions.

Lowry did not tell Carol in advance about her extraordinary legacy.

It was entirely in keeping, of course, that even the woman who could claim to know him best was to find herself astonished

by her inheritance and the complexity that it revealed.

'I was shocked, really shocked,' she says. 'It took several years before it hit me properly.'

'He told me he would leave me his piano and sideboard, and that is what I thought I would get. I don't know why he left it all to me.'

Erotic secrets that prove he was ahead of his time

Mail on Sunday Art Critic Philip Hensher says the new pictures actually enhance Lowry's reputation

L.S. Lowry, despite his immense public popularity, has never quite attained the highest repute.

Even the opening of the £106million arts centre The Lowry, in Salford Quays, in 1999 didn't manage to raise him into the

pantheon of 20th Century artists.

Lowry remains popular, rather than important; it's hard to imagine Tate Britain, which has 23 Lowrys in its basement,

mounting a survey of his work.

Chris Stephens, head of display at Tate Britain, explains, 'To some extent Lowry is a victim of his fan base.

The same qualities that make him popular are those that cause him to be less seriously celebrated by the artistic establishment.'

Futuristic; Secret desires appear to be the driving force behind these images made at the end of his life.

Such artists often have the last laugh, surviving better than many a loud reputation.

Discoveries about Lowry's work since his death in 1976 are making him seem more complicated and expressive than had been suspected.

This ITV documentary has brought off a coup in persuading Carol Ann Lowry to speak for the first time about her relationship with the painter.

But it has performed a bigger one in revealing some private works by Lowry that uncover unexpected personal imagery.

They are full of his desire and pain.

Few painters' names evoke so immediately a particular sort of painting as Lowry's.

A Lowry is an industrial townscape, normally in closely limited tones of grey and brown, reduced to geometric cubes and lines.

They are often thickly populated by Lowry's most famous feature, the 'matchstick men and matchstick cats and dogs' celebrated in a pop song.

However many figures Lowry includes, they remain stylised, regular, dehumanised; his paintings, as he said himself, have a quality of loneliness.

It would be easy to assume, from such simplicity, that Lowry was an untutored, 'naive' painter. He was not. He consciously created his naive style.

In fact, he came from a sophisticated and cosmopolitan school of painters, and was taught at the Manchester Municipal School of Art

by impressionist Adolphe Valette.

Surprising corners of his work have emerged. An anguished series of self portraits from the Thirties have become well known.

The 1957 Portrait Of Ann was a startling departure from 'Lowry' style.

Now he turns out to have created some deeply private, erotically tinged images.

Some were exhibited at the Barbican in 1988, causing a stir. Carol Ann Lowry talks about the ones she was bequeathed in this documentary.

Lowry was not the first to create erotic art for his own or friends' amusement.

Some artists were not far from pornographers, while others created specialised fare for a particular client.

But in other cases, secret desires appear to be the driving force. Lowry's drawings seem to be of this sort.

They are fascinating partly because the desires seem so peculiar, but also because they force Lowry into new expressive areas.

He appears, for once, to be ahead of his time.

These strikingly geometric compositions depict young women constrained into bizarre, restrictive costumes, their soft flesh turned

into machinery by impossible clothing.

Their bodies are corseted in tube like contraptions; their collars rise, cutting into their cheeks and faces.

Sometimes an enormous Edwardian bow rises, concealing their faces like a gag.

There is a degree of sexual fantasy behind these works, why else hide them away?

But that is not their most interesting aspect.

In creating these images, he ventured into areas where the human body becomes mechanised;

where women, modified by male fantasy, turn into efficient machinery.

Some of these images anticipate, or run alongside, the styles of Sixties Pop Art.

I am reminded of the work of controversial Pop artist Allen Jones.

Nobody at the time would have thought of Lowry as occupying the forefront of artistic fashion.

But in private, he was doing exactly that. He seems, more and more, like a rather interesting artist.

LSLowry died aged 88 in 1976 just months before a retrospective exhibition of his paintings opened at the Royal Academy. It broke all attendance records for a twentieth century artist. Critical opinion about Lowry remains divided to this day. Salford Museum & Art Gallery began collecting the artist's work in 1936 and gradually built up the collection which is now at the heart of the award-winning building bearing the artist's name. Celebrating his art and transforming the cityscape again. A small quantity of paintings by the artist l.s. lowry were published as signed limited edition prints. Some of the most well known being, 'Going to the match', Man lying on a wall, Huddersfield, Deal, ferry boats, three cats Alstow, Berwick-on-Tweed, peel park, The two brothers, View of a town, Street scene.

You may find some of our other websites of particular interest; the signed limited edition prints and paintings by wildlife artist David Shepherd,Also the work of Sir William Russell Flint whose paintings and signed limited edition prints are in great demand.

Famous for his portraits of Cecilia, Flint's greastest works illustrate the architecture and landscape throughout rural France

This holiday house near Brantome, in the area of Dordogne is ideally situated to enjoy the France.

The work of Mr L.S. Lowry has become of great artistic and financial importance of recent years. A selection of his signed prints and originaldrawings can be viewed and bought here

Our aim is to offer our clients an excellent service at unbeatable prices.